Bat Cave Preserve – Home – Parks & Forests – Camping – Hiking – Links – Adventures

Back to Outdoors Advocacy & Support Groups

Bat Cave Preserve

As the name implies, several species of bat make their home in Bat Cave, including the endangered Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis). Ours was one of the last public visits to Bat Cave, the largest augen gneiss granite fissure cave in the world and the focus of 275 acres owned by the North Carolina Nature Conservancy in Hickory Nut Gorge.

Little more than a week after we were there, the Nature Conservancy banned all entry to Bat Cave to guard against the spread of white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has wiped out millions of bats in North America (in at least 29 states and five Canadian provinces) since 2007. The Conservancy’s staff also avoid the area in winter months to give the bats their best chance at hibernating successfully and undisturbed through the winter.

We hiked up to to Bat Cave on a Sunday in May 2009 with Dana Redfield, a Nature Conservancy volunteer.

Dana Redfield

Prior to the ban, volunteers like Dana led hikes at the preserve during the summer. Even then, because even human body temperature can damage the habitat, visitors were only allowed in the 300-foot entrance hall to Bat Cave (below) and in a smaller chamber called Little Bat Cave.

Dana approaches Little Bat Cave …

Bat Cave has been known by generations in the southwest North Carolina mountains, and is even at the center of a couple of myths involving Indians and stolen gold. But it was pretty much ignored scientifically until the 1970s, and it wasn’t until the 1980s that researchers realized the Bat Cave system is more than a mile long, making it the world’s largest granite fissure cave.

Fissure caves are formed by movements of the earth – earthquakes and other shifts – as opposed to erosion, which forms most caves, including the limestone caves prevalent in the Southeast. The rock in Bat Cave is augen gneiss, a granite formed about 535 million years ago during the Cambrian period, according to the Nature Conservancy.

At the time of our hike, Nature Conservancy volunteers and staff entered the cave every three years to inventory the bats, coming up with about 175 on the most recent count, according to Dana, who participated in the count. From October to mid-April, the preserve is closed so that the bats’ hibernation is not disturbed; a gate at the bridge over the Rocky Broad River (below) controls access. If the bats are awakened, Dana explained, they will search for food and not find it, but in the process burn energy they need to live through the winter.

From the Rocky Broad River, the trail climbs through fine examples of a rich cove forest, usually found at higher elevations but here because of the Hickory Nut Gorge’s cool, moist conditions; and an acidic cove forest, which is typical of steep gorges. Presence of the two types of forests causes Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana), chestnut oak (Quercus prinus) and Rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum) to grow nearly side-by-side. “The rich cove and acidic cove forest, the preserve is such a great example of that because it’s so obvious,” Dana said. “We do a lot of non-native species removal, so it’s like a North Carolina forest would be if there wasn’t (for example) kudzu and other invasives.”

Dana points out some rhododendron …

Because of the work done by volunteers like Dana, the preserve also sustains many spring wildflowers, including bloodroot, toothwort, phacelias and several species of trillium (which, except for some trillium, were not much in bloom the day we were there). There are also many types of ferns, including walking fern (Asplenium rhizophyllum), Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides) and marginal woodfern (Dryopteris marginalis); several varieties of alumroot (Heuchera americana) and several endangered plants, including broadleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis latifolia) and Carey’s saxifrage (Saxifraga careyana).

Walking fern

Our first stop on the hike was a seepage pool where Dana spotted what she thought was a small “crevice salamander” that is only found in Hickory Nut Gorge. Originally considered a separate species, they are now known as the Bat Cave form of the Yonahlossee salamander (Plethodon yonahlossee). Another source tell us this salamander is actually a seal salamander (Desmognathus monticola), which is found throughout the central and southern Appalachians.

A highlight for many hikers are the Bat Cave blowholes, cracks in the granite wall at the foot of the larger cave (below) where air that has fallen from the top of the ridge and been chilled by the damp cave seeps out. On warmer days, the contrast between the forest’s heat and humidity and the cave’s constant 50 degrees makes a spot in front of a blowhole pleasant.

Some of the flora found at Bat Cave Preserve …

Mayapple looking pixilated

Galax growing trailside

Bellwort

Ginger

Mushrooms on the horizon

Trillium

Wild Hydrangea

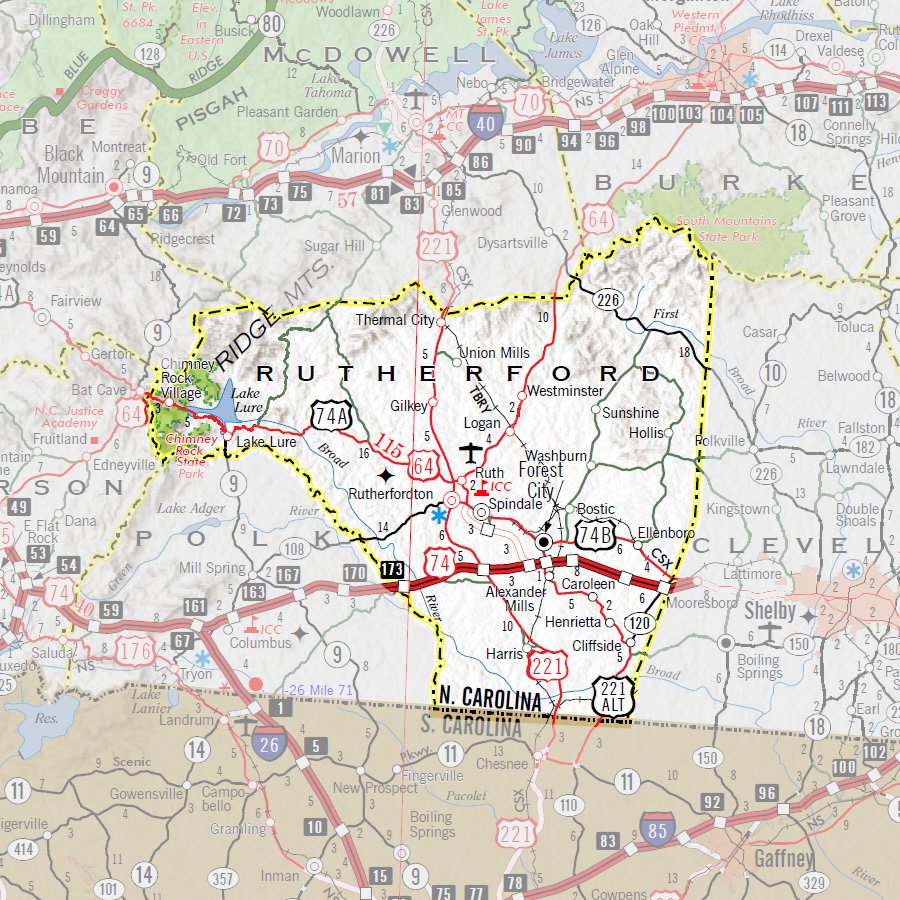

Bat Cave preserve is in Rutherford and Henderson counties, near Chimney Rock and Chimney Rock State Park.

Check with the N.C. Nature Conservancy about public access.

Return to Outdoors Advocacy & Support Groups.

Visit Our Sister Site

Carolina Music Festivals, a calendar and guide to music festivals in North Carolina.